“O desenvolvimento é uma viagem

com mais náufragos do que navegantes.”

Eduardo Galeano,

Las Venas Abiertas de América Latina

No mesmo ano de 1492 em que os conquistadores espanhóis aportaram nas praias do chamado Novo Mundo, a Espanha expulsou 150 mil judeus de seu território e re-conquistou Granada, arrancando-a das garras dos muçulmanos. As Monarquias Absolutas da península ibérica, calcadas na dogmática católica – em especial aquela falaciosa ideologia hoje quase completamente enterrada em descrédito do “monarca por decreto divino” – estavam envolvidas nas turbulências de guerras religiosas sanguinolentas. Quem chegou às Américas em 1492 não foram alguns cristãos pacifistas e benevolentes, como logo descobririam as populações nativas. Os índios não tardaram a fazer uma péssima descoberta: os invasores provinham de civilizações européias cujas elites dirigentes sabiam ser extremamente violentas, intolerantes, dogmáticas e embevecidas por delírios de etno-superioridade. Relembrando aqueles tempos, Galeano escreve:

“A Espanha adquiria realidade como nação erguendo espadas cujas empunhaduras traziam o signo da cruz. A rainha Isabel fez-se madrinha da Santa Inquisição. A façanha do descobrimento da América não poderia se explicar sem a tradição militar da guerra das cruzadas que imperava na Castela medieval, e a Igreja não se fez de rogada para atribuir caráter sagrado à conquista de terras incógnitas do outro lado do mar…” [Nota #1]

Em 1492, os milhões de habitantes deste continente que o invasor estrangeiro depois batizaria de América tiveram um encontro traumático: “descobriram que eram índios, que viviam na América, que estavam nus, que existia o pecado, que deviam obediência a um rei e a uma rainha de outro mundo e a um deus de outro céu, e que este deus havia inventado a culpa e a vestimenta, e havia ordenado que fosse queimado quem quer que adorasse o sol, a lua, a terra e a chuva que a molha…” (Galeano)

Corte para maio de 2007. O Papa visita o Brasil e discursa na basílica de Aparecida (custo desta construção: 37 milhões de reais). Joseph Ratzinger, o Bento XVI, autoridade-mor da Cristandade no princípio do 21º século depois do nascimento do Nazareno, pontifica:

Corte para maio de 2007. O Papa visita o Brasil e discursa na basílica de Aparecida (custo desta construção: 37 milhões de reais). Joseph Ratzinger, o Bento XVI, autoridade-mor da Cristandade no princípio do 21º século depois do nascimento do Nazareno, pontifica:

“A fé cristã encorajou a vida e a cultura desses povos indígenas durante mais de 5 séculos. O anúncio de Jesus e de seu Evangelho nunca supôs, em nenhum momento, uma alienação das culturas pré-colombianas, nem uma imposição de uma cultura estrangeira. O que significou a aceitação da fé cristã pelos povos da América Latina e do Caribe? Para eles, isso significou conhecer e aceitar o Cristo, esse Deus desconhecido que seus antepassados, sem perceber, buscavam em suas ricas tradições religiosas. O Cristo era o Salvador que eles desejavam silenciosamente.” [Nota #2]

Comparados, os discursos de Galeano e de Ratzinger são explicitamente contraditórios, antagônicos, irreconciliáveis. Não há como ambos possam estar certos simultaneamente – o que equivale a dizer que, destes dois, um deles mente. A história da Conquista que nos narra o autor d’As Veias Abertas Da América Latina é repleta de chacinas, pilhagens e horrores; nela houve sim, indubitavelmente, uma cultura forçada goela abaixo dos nativos através da violência das armas-de-fogo e das espadas afiadas. Já a história, higienizada pelo Papa (que demitiu-se, dando lugar ao Papa Chico), fabrica um conto-de-fadas: nele, a fé cristã foi “aceita” na América por aqueles que “desejavam silenciosamente” abraçar o Cristo, e segundo Bento XVI os europeus que aportaram no Novo Mundo agiram de modo humanitário e generoso ao presentear os pagãos com a imensa benesse de seu catolicismo.

Diante da lorota papal, Jean Ziegler comenta, em Ódio ao Ocidente: “Raramente uma mentira histórica foi proferida com tanto sangue-frio. […] A população total de astecas, incas e maias era de 70 a 90 milhões de pessoas quando os conquistadores chegaram. Entretanto, um século e meio depois, restavam apenas 3,5 milhões.” [Nota #3]

A cidade de Potosí, na Bolívia, serve como um exemplo das ações dos predadores ibéricos e seu apetite voraz pelas riquezas alheias. Potosí, que fica a quase 4.000 metros de altitude, já foi uma das cidades mais populosas e ricas do mundo. No século XV e XVI, torna-se tamanho paradigma de um território abençoado com vastas riquezas naturais a ponto de no romance clássico de Cervantes, Dom Quixote de La Mancha, o Cavaleiro da Triste Figura utilizar-se, em seus papos com Sancho Pança, a expressão “vale um Potosí”. Os invasores estrangeiros extraíram, durante 3 séculos, cerca de 40.000 toneladas de prata de suas montanhas [nota #4].

As comunidades quíchua e aimará do Altiplano andino foram escravizadas, empurradas para as minas e coagidas por guardas armados ao labor pesado em circunstâncias adversas. Os desabamentos eram frequentes e muitos mitayos (os escravos mineiros) acabavam enterrados vivos nas profundezas da montanha de prata. Estima-se que 8 milhões de pessoas morreram em Potosí no processo de butim que os invasores europeus promoveram. Para justificar o genocídio, o teólogo espanhol Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda (1489-1573) explica: “Os indígenas merecem ser tratados dessa maneira porque seus pecados e idolatrias ofendem a Deus.” Em outras palavras: na teologia imperial, Deus é espanhol, ama o capitalismo e aplaude a escravização e a chacina.

Potosí é apenas um caso dentre muitos outros e poderíamos contar uma estória semelhante sobre as Minas Gerais, em especial Vila Rica, hoje Ouro Preto, que foi pilhada de todo o seu ouro, assim como Potosí foi assaltada de toda a sua prata. Ao invés de multiplicar exemplos de horrores que sucederam à Conquista da América, ouçamos esta reflexão mais geral de Karl Marx sobre as conexões entre o desenvolvimento do capitalismo industrial europeu e o empreendimento colonial, escravocrata e genocida:

“O capital veio ao mundo suando sangue e lama por todos os poros. […] Em geral, a escravidão velada dos operários assalariados na Europa precisava, como pedestal, da escravatura notória no Novo Mundo. […] O tesouro capturado fora da Europa, diretamente por pilhagem, escravização, assassinato seguido de roubo, refluiu para a mãe pátria e transformou-se aí em capital.” [nota #5]

Em sua aurora, portanto, o capitalismo europeu nutriu-se de holocaustos coloniais, praticou a escravização em massa, sugou suas gordas mais-valias da exploração brutal do trabalho forçado, com as bênçãos de papas e reis. O que se seguiu à Conquista da América, aquilo de que ainda somos infelizmente contemporâneos, é uma história-ainda-presente de genocídio e etnocídio, entrelaçados e amalgamados. Não foi Hitler quem inventou a limpeza étnica. Os índios conheceram-na a partir de 1492 e talvez não haja absurdo algum em chamar a coisa por seu devido nome: holocausto. Em Arqueologia da Violência, Pierre Clastres explana o que entende pela palavra “etnocídio” e no que esta se distingue de “genocídio”: “O etnocídio é a supressão das diferenças culturais julgadas inferiores e más; é a aplicação de um projeto de redução do outro ao mesmo…” Ouçamos mais longamente à argumentação de Clastres:

“Quem são os praticantes do etnocídio? Em primeiro lugar, aparecem na América do Sul, mas também em muitas outras regiões, os missionários. Propagadores militantes da fé cristã, eles se esforçam por substituir as crenças bárbaras dos pagãos pela religião do Ocidente. A atitude evangelizadora implica duas certezas: primeiro, que a diferença – o paganismo – é inaceitável e deve ser recusada; a seguir, que o mal dessa má diferença pode ser atenuado ou mesmo abolido. É nisto que a atitude etnocida é sobretudo otimista: o Outro, mau no ponto de partida, é suposto perfectível, reconhecem-lhe os meios de se alçar, por identificação, à perfeição que o cristianismo representa.

O etnocídio é praticado para o bem do selvagem. O discurso leigo não diz outra coisa quando enuncia, por exemplo, a doutrina oficial do governo brasileiro quanto à política indigenista: “Nossos índios, proclamam os responsáveis, são seres humanos como os outros. Mas a vida selvagem que levam nas florestas os condena à miséria e à infelicidade. É nosso dever ajudá-los a libertar-se da servidão. Eles têm o direito de se elevar à dignidade de cidadãos brasileiros, a fim de participar plenamente do desenvolvimento da sociedade nacional e de usufruir de seus benefícios”. A espiritualidade do etnocídio é a ética do humanismo.

Denomina-se etnocentrismo a vocação para avaliar as diferenças pelo padrão da sua própria cultura. O Ocidente seria etnocida porque é etnocentrista, porque se pensa e quer ser a civilização. […] O etnocídio é a supressão das diferenças culturais julgadas inferiores e más; é a aplicação de um projeto de redução do outro ao mesmo. O índio amazônico suprimido como outro e reduzido ao mesmo como cidadão brasileiro. Em outras palavras, o etnocídio resulta na dissolução do múltiplo em Um.” [nota #6]

Ora, a Conquista da América foi um projeto genocida e etnocida, posto em prática por potências imperiais européias que chegaram aqui embevecidas com sua intolerância, embrutecidas por sua presunção de superioridade.

No filme espanhol Também A Chuva (También La Lluvia), da Iciar Bollain, temos a oportunidade de refletir sobre imperialismo e colonização em um contexto visceralmente contemporâneo: estamos na Bolívia do começo do século, às vésperas da eclosão da Guerra da Água de Cochabamba.

Gael Garcia Bernal encarna um dos espanhóis da equipe de produção do filme-dentro-do-filme, um desses blockbusters que pretendem fornecer um retrato épico e heróico da História. Pagam uma merreca para que os bolivianos participem como figurantes das filmagens e pretendem ordenar os rumos da película como se fossem ainda os poderosos chefões de outrora.

Só que as ebulições do presente suplantam o retrato sereno do passado: a equipe cinematográfica que queria apenas realizar um filme sobre os tempos de Colombo acaba envolvida pelo turbilhão da imensa revolta popular que seguiu-se à decisão, tomada pelo conluio governamental-corporativo, de privatizar a água na Bolívia.

O título do filme – Também a Chuva – refere-se a algo que até parece mentira, invenção satírica, paranóia de Bolivarista: a privatização de todas as formas de água, inclusive a da chuva. Ocorreu de fato: os bolivianos não só tiveram que engolir um aumento de 300% nas tarifas da água, após o cerceamento corporativo do commons; os bolivianos tiveram roubado até mesmo seu direito à chuva.

Em nossa era dita “neoliberal” (mas que talvez merecesse o nome “neocolonial”), a América Latina ainda batalha contra os gigantes do capitalismo global que aqui desejam faturar seus imensos lucros ao preço de nossa imensa miséria: na Bolívia, o acordo entre as mega-corporações transnacionais e o Estado elitista que as servia de joelhos, na era pré-Evo Morales, fez com que este direito humano básico à água, esta necessidade elementar para a sobrevivência física de qualquer ser humano, fosse transformado em mercadoria e pretexto para o lucro.

Fotos extraídas do artigo de Franck Poupeau, “La guerre de l’ eau – Cochabamba, Bolivie, 1999-2001” (Pg. 133 do seguinte livro, disponível em PDF: http://agone.org/lyber_pdf/lyber_401.pdf)

Assim que a privatização da água foi imposta pelo governo e efetivada pelas corporações, o que ocorreu foi que as empresas capitalistas

“aumentaram massivamente o preço da água potável e centenas de milhares de famílias viram-se na impossibilidade de pagar a conta. Elas tiveram que se abastecer nos riachos poluídos, nos poços envenenados pelo arsênico. As mortes infantis pela ‘diarreia sangrenta’ aumentaram potencialmente. Manifestações públicas começaram a explodir. Durante os confrontos com a polícia, dezenas de pessoas foram mortas e centenas ficaram feridas, entre elas muitas mulheres e crianças. Mas os bolivianos não se dobraram. O movimento se espalhou por todo o país. No dia 17 de outubro de 2003, cercados no palácio Quemado por uma multidão enfurecida de mais de 200 mil manifestantes, o presidente Lozada e seus comparsas mais próximos decidiram fugir do país. Destino: Miami.” [nota #7]

Também a Chuva tem entre seus méritos maiores o retrato destes eventos cruciais na história latino-americana recente. A excelência do filme está no modo como ele procura compreender o presente sempre vinculado ao passado histórico, estabelecendo paralelos eloquentes entre as atitudes de Cristóvão Colombo e seus asseclas, outrora, e dos novos conquistadores do capitalismo globalizado: ambos decretam-se os donos e os possuidores de recursos naturais, aos quais pretendem ter direito por terem sido escolhidos por Deus-Pai ou pelo Deus-Progresso (este último, diga-se de passagem, como nos lembrou a epígrafe Galeaneana deste texto, “é uma viagem com mais náufragos que navegantes…”).

Contando com mais uma atuação brilhante de Gael Garcia Bernal (que iluminou-nos e cativou-nos sobre a história latino americana também em filmes como No de Pablo Larraín e Diários de Motocicleta de Walter Salles), Também a Chuva é um dos melhores filmes a explorar a complexidade de nossa história recente, sendo dotado de uma vibe próxima à dos clássicos de cineastas como Gillo Pontecorvo (A Batalha de Argel, Quemada!) e Roland Joffé (A Missão, Os Gritos do Silêncio). É um filme que ajuda-nos a compreender as novas revoluções bolivaristas do continente sob a perspectiva daqueles que conquistaram, em especial na Bolívia e na Venezuela, algumas das mais significativas vitórias do movimento dito “altermundialista” nas últimas décadas.

O filme permite-nos entender o processo que conduziu a Bolívia a livrar-se do jugo de corporações (como a Bechtel e a Suez) e presidentes (como Lozada ou Banzer) que eram fanáticos praticantes da política “Privatização de Tudo” . Contestados e destronados, estes representantes do neo-imperialismo sofreram um revés com a eleição de Evo Morales em 2006, o primeiro presidente de raízes indígenas a ser eleito democraticamente na América Latina. Pachamama renasceu das cinzas. E com ela as centelhas de esperança.

Se as ocorrências em Cochabamba são tão relevantes para nosso presente e nosso futuro, acredito que é porque não escaparemos a um porvir onde os antagonismos e conflitos relacionados com a água vão se exacerbar e intensificar. A pior seca da história de São Paulo, por exemplo, já inspira alguns dos melhores analistas políticos brasileiros, como Guilherme Boulos (militante do MTST), a perguntar/provocar: “há quinze anos, na Bolívia, atitudes semelhantes às adotadas agora por Geraldo Alckmin provocaram levante popular. É isso que governador deseja produzir?” [nota #8]

Escrevendo no calor da hora, em novembro de 2000, Arundhati Roy reflete sobre a Batalha de Cochabamba como um símbolo de como opera atualmente o capitalismo oniprivatizante e como este é contestado por insurreições grassroots; em seu artigo Power Politics: The Reincarnation of Rumpelstiltskin, a escritora e ativista indiana escreve:

“What happens when you ‘privatise’ something as essential to human survival as water? What happens when you commodify water and say that only those who can come up with the cash to pay the ‘market price’ can have it? In 1999, the government of Bolivia privatised the public water supply system in the city of Cochacomba, and signed a 40-year lease with Bechtel, a giant US engineering firm.The first thing Bechtel did was to triple the price of water. Hundreds of thousands of people simply couldn’t afford it any more. Citizens came out on the streets to protest. A transport strike brought the entire city to a standstill. Hugo Banzer, the former Bolivian dictator (now the President) ordered the police to fire at the crowds. Six people were killed, 175 injured and two children blinded. The protest continued because people had no options—what’s the option to thirst? In April 2000, Banzer declared Martial Law. The protest continued. Eventually Bechtel was forced to flee its offices. Now it’s trying to extort a $12-million exit payment from the Bolivian government…” [nota #9]

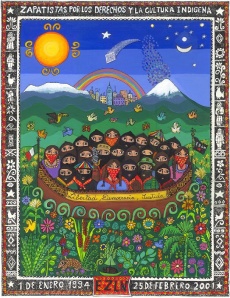

Vale relembrar que a Bolívia do começo dos anos 1990 já havia dado sinais claros de que, naquelas terras de onde surrupiaram-se toneladas de prata de Potosí, naquelas terra onde o médico-gerrilheiro Che Guevara foi assassinado, a rebelião não dormia nem estava morta. Em 1992, por ocasião dos 500 anos do início da Conquista da América, iria acontecer em La Paz uma “suntuosa festa de aniversário” organizada pelas autoridades branquelas, com desfile militar, cerimônias diplomáticas, convidados vindos da Europa, coms Te Deums e améns destinados a celebrar a ideologia de uma colonizadores europeus, humanitários e filantrópicos, que fizeram o favor de nos trazer a verdadeira civilização – lorota que o imperialismo deseja inscrever como dogma em nossos livros, monumentos, consciências.

O espírito de resistência e insurgência, esse ímpeto revoltado à la Tupac Amaru, renasceu para mostrar que “nunca, durante esses últimos cinco séculos, a brasa se apagou debaixo das cinzas”, como escreve Jean Ziegler. Emergindo dos indígenas, que constituem mais de metade da população do país, nasceu um protesto colossal: “Várias centenas de milhares de aimarás, quíchuas, moxos e guaranís (…) vaiaram Cristóvão Colombo, derrubaram as tribunas de honra e ocuparam a capital durante quatro dias. Na manhã do quinto dia, pacificamente, voltaram para suas comunidades no Altiplano…” [nota #10]

Eis aí, pois, na Bolívia, algumas inspiradoras estórias de desobediência civil contestatória e mobilização transformadora. Thoreau e Gandhi aplaudiriam Cochabamba? Relembrar isto tudo, aprofundar os estudos sobre estes episódios, serve para a tarefa essencial de pôr em questão a história oficial e escrever em seu lugar uma história mais múltipla, que abrigue a voz e as lutas daqueles que podem até ser considerados por alguns como sendo parte de nosso passado. Em Até a Chuva, o político pontifica que, “se deixarmos, esses índios vão nos levar de volta à Idade da Pedra”. Ora, aqueles que alguns julgam como sobreviventes do passado talvez sejam, na verdade, os guias essenciais para nosso futuro. Se um outro mundo é possível e necessário, é preciso lembrar que uma outra história também é possível e necessária, como Walter Benjamin sugeria em 1940, nas Teses Sobre o Conceito de História, em que ele aponta: “em cada época é preciso arrancar a tradição ao conformismo que quer apoderar-se dela” e “despertar no passado as centelhas da esperança” [nota #11].

Na Bolívia, imensos protestos contra a privatização da água tomaram conta das ruas de Cochabamba em 2000.

E.C.M.

Goiânia, Dez 2014

* * * * *

REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

1. GALEANO, Eduardo. As Veias Abertas da América Latina. Capítulo: Febro do Ouro, Febre da Prata. Sub-capítulo: O signo da cruz nas empunhaduras das espadas. Trad. Sergico Faraco. Ed. L&PM. 2010. Pg. 30.

2. Le Monde, 15 de maio de 2007

3. ZIEGLER, Jean. Ódio ao Ocidente. Ed. Cortez, 2008, p. 188.

4. HAMILTON, Earl J. American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, 1501-1650. Massachusetts, 1934.

5. MARX, Karl. Oeuvres Complètes, editadas por M. Rubel. Vol. II: Le Capital, tomo I, seção VIII. Paris: Gallimard. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

6. CLASTRES, Pierre. Arqueologia da Violência – Pesquisas de Antropologia Política. Ed. Cosac & Naify, 2004.

7. ZIEGLER. Op cit [nota#3], 2011, p. 208.

8. BOULOS, Guilherme. São Paulo Rumo A Uma Guerra da Água?. Leia o artigo completo no Outras Palavras.

9. ROY, Arundhati. Power Politics: The Reincarnation of Rumpelstiltskin. Leia o artigo completo na Outlook India, 27 de Novembro de 2000.

10. ZIEGLER. Op cit. P. 206-207.

11. BENJAMIN, Walter. Sexta Tese Sobre o Conceito de História. In: Obras Escolhidas I – Magia e Técnica, Arte e Política. Ed. Brasiliense, pg. 225.

* * * * *

Veja também:

Abuella Grillo (2009)