Bat in Flower – A pollen-gilded bat emerging from a flower of the blue mahoe tree, in Cuba. Photograph by Merlin Tuttle, National Geographic.

“What Is It Like To Be A Bat?”

by Eduardo Carli de Moraes

In one of the greatest essays in his book Mortal Questions, Thomas Nagel invites us to reflect in a daring and innovative way, as awe-inspiring as the best Science Fiction films or novels. Forget about mankind for a while and try to identify yourself with the perspective of an animal that’s quite different from bipeds and primates such as ourselves. Put yourself inside the skin of a bat, but not only in a cartoonish or playful way (don’t even waste time pretending you are Bruce Wayne, wearing a black costume and a horned mask, patrolling Gotham City in search of criminals to crush).

Nagel is asking us to attempt to become a bat as it really is in Nature’s web of life: how does it feel to be such a creature? What Nagel is proposing is an exercise in which a human mind tries to move away from its humanness, venturing outside the zone of familiarity, trying to really grasp what sort of experience it would be like to exist as a bat – or an eagle, or a worm. That ain’t easy, and “philosophers share the general human weakness for explanations of what is incomprehensible in terms suited for what is familiar and well understood.” (pg. 166)

This is not just a role-playing game (“let’s pretend we’re animals, let’s meow like cats!”), nor it’s a creative phantasy which attemps to imagine the future (similarly to what was crafted with such greatness by David Cronenberg‘s The Fly). What Thomas Nagel is after with his sci-fi way-of-thinking, as I’ll further attempt to explore, is an explanation for consciousness and its great diversity of manifestations. Reality contains objectively myriads of different organisms, with different perspectives and subjective experiences, and this field of study – Nature’s richness and diversity – may be explored not only by poets, mystics or people high on LSD, but also by philosophers, physicists, scientists, artists… Maybe we’ll become better humans if we try to understand better what is it like not to be human?

“Conscious experience is a widespread phenomenon. It occurs at many levels of animal life, though we cannot be sure of its presence in the simpler organisms, and it is very difficult to say in general what provides evidence of it. (Some extremists have been prepared to deny it even of mammals other than man.) No doubt it occurs in countless forms totally unimaginable to us, on other planets in other solar systems throughout the universe. But no matter how the form may vary, the fact that an organism has conscious experience at all means, basically, that there is something it is like to be that organism. (…) We may call this the subjective character of experience…” (p. 166)

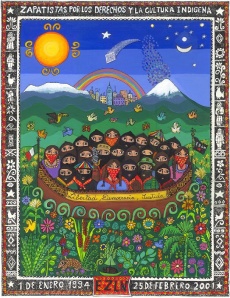

Those among you, dear readers, who are not poetically inclined, may deem as utter philosophical madness to refer to such a thing as “the subjectivity of bats” or the conscious experience of pigs. But it’s been for centuries the self-imposed task and delight of poets, mystics, shamans, artists, as well as many other human animals, to understand and try to verbalize what it means like to be an animal different than ourselves. William Blake, for example, had a fruitful relationship with flies, as you’ll see in the following poem, and he also sung with his lyre some quite fascinating stuff about dogs, horses and skylarks:

“Little Fly,

Thy summer’s play

My thoughtless hand

Has brush’d away.

Am not I

A fly like thee?

Or art not thou

A man like me?

For I dance,

And drink, and sing,

Till some blind hand

Shall brush my wing…”

* * * *

“A dog starved at his master’s gate

Predicts the ruin of the State.

A horse misus’d upon the road

Calls to Heaven for human blood.

Each outcry of the hunted hare

A fibre from the brain does tear.

A skylark wounded in the wing,

A cherubim does cease to sing…”

WILLIAM BLAKE

Thomas Nagel is interested in exploring the idea of animals as beings who experience the world from a different perspective, from a subjective standpoint which differs greatly according to the organism’s complexity and to the various environments that it inhabits. For example, a polar bear and a huge whale like Moby Dick have very different conscious experiences because they’re living where they do: the first in freezing snowy temperatures, the latter beneath the oceans’s rolling waves. But let’s go back to Nagel’s bats:

“I assume all believe that bats have experience. After all, they are mammals, and there is no more doubt that they have experience than that mice or pigeons or whales have experience. (…) Bats, although closely related to us, nevertheless present a range of activity and a sensory apparatus so different from ours that the problem I want to pose is exceptionally vivid (though it certainly could be raised with other species). Now we know that most bats perceive the external world primarily by sonar, or echolocation, detecting the reflections, from objects within range, of their own rapid, subtly modulated, high-frequency shrieks. Their brains are designed to correlate the outgoing impulses with the subsequent echoes, and the information thus acquired enables bats to make precise discriminations of distance, size, shape, motion and texture – comparable to those we make by vision.” (pg. 168)

These fascinating and scary creatures, winged mammals who fly speedily in the air, even though they can’t see anything (thus the expression “blind as a bat”), have an existential experience which is quite hard for a human to imagine and that it’s impossible for us to really “live”. How is it like, subjectively, to fly around being a bat and using a sonar for sight? Does our imagination really permit us to truly experience Batness?

And how to avoid scenes of Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, or from the Batman comics, from messing-up our experiment, by appearing on our Hollywood-colonized human-minds, everytime we think of men and bats?

Imagination is limited and usually binds us to a human perspective, argues Thomas Nagel, and to experience what truly is the subjective consciousness of a bat it’s not enough “that one spends the day hanging upside down by one’s feet in an attic.” (pg. 169) Now we’re getting closer to his point: Nagel wants to know “what it is like for a bat to be a bat.” (p. 169)

There seems to exist an abyss of ignorance separating each species, though they all belong to the one and the same Web of Life. We might call this the Abyss of Alterity, but maybe someone needs to be a poet or a mystic to grasp what that means. Thomas Nagel paints a portrait of such an abyss, one we are seldom able to cross, when he writes about men and bats: humans can’t know what it’s like to be inside the skin of a bat, and neither the bat has a clue about how the heck it feels to be a primate such as ourselves. Simply because there’s no bridge that can serve as a means of transportation, from human experience right into bat experience, and vice versa: “even if I could by gradual degrees be transformed into a bat, nothing in my present constitution enables me to imagine what the experiences of such a future stage of myself thus metamorphosed would be like.” (p. 169)

Even an imagination so powerfull and daring as Franz Kafka’s could only reach an anthropomorphized report of what it meant for Gregor Samsa to discover himself living inside the body of a bug. However, for Gregor Samsa, a human mind and a human consciousness are still locked inside the beastly body that he wakes up, in Kafka’s masterpiece The Metamorphosis, suddenly transformed into.

Thomas Nagel knows perfectly well that one can’t become a bat after being born a monkey, a wolf, a bacteria or a human being, but he also states that human imagination fails to give us any true depiction of the specific subjective character of the experienced subjectivity of creatures of other species – “it’s beyond our ability to conceive.” (p. 170)

This sets, methinks, epistemology in new grounds and adds a new chapter to the history of Skepticism in philosophy. Nagel’s highly skeptical conclusion – we’ll never really experience what it’s like to be an animal different than the animal we are – also spreads into his consideration of human affairs, where similar abysses of mutual ignorance also exist. For example: “The subjective character of the experience of a person deaf and blind from birth is not accessible to me, nor presumably is mine to him. This does not prevent us each from believing that the other’s experience has such a subjective character.” (p. 170)

If we’re ever to meet extra-terrestrial organisms – be they iron-headed Martians, bizarre aliens from Titan, or other weird creatures from a far-away galaxy… – the same problem would certainly arise: the aliens wouldn’t have a clear perception of what it is like to be a human. Similarly, it would remain as an obstacle for dialogue with the aliens the fact of our human difficulty – or even incapacity – to truly understand what it is like to be a bat or a whale, a butterfly or an eagle, a worm or a Martian.

Subjectivity, thus, is so highly varied in its manifestations, in its different incarnations, that we must revise our concepts and renew our vocabulary: “subjective” shouldn’t mean only “the personal self”, but some sort of existential perspective that exists in myriads of different ways according to the varied organisms and environments. This “enormous amount of variation and complexity” can be partially explained by Darwin’s theory of Evolution, but what Thomas Nagel seems to be pointing out is this: reality is too complex, its multiplicity is too great, for a mind such as ours, with a language such as we have developed so far, to truly understand it. We’re incapable of an understanding that embraces all subjective conscious experiences of all living beings. This is one of the main problems Nagel’s philosophy deals with, especially in the excellent and mind-boggling philosophy-ride of his book View From Nowhere.

Buy The View From Nowhere at Amazon

“The fact that we cannot expect ever to accommodate in our language a detailed description of Martian or bat phenomenology should not lead us to dismiss as meaningless the claim that bats and Martians have experiences fully comparable in richness of detail to our own. It would be fine if someone were to develop concepts and a theory that enabled us to think about those things; but such an understanding may be permanently denied to us by the limits of our nature.” (pg. 170)

Some sort of disconnection between the human animals and the Animal Kingdom as a whole seems to arise, Thomas Nagel argues, from our mind’s incapacity to truly understand any subjective experience that differs too much from ours. This can’t be explained only by biology, by processes of Natural Selection, because Culture intervenes and imposes its systems, its symbols, its values.

In a civilization, for example, where in thousands of supermarkets one can buy the meat of recently killed animals, already packed, frozen and wrapped in plastics, people tend to dissociate their minds from any sort of empathy with pigs, cows or chickens. When it’s barbecue time and the dead bodies of recently killed animals are being grilled, people tend to never think about the slaughterhouses. People rarely pay any mind to what life feels like, when lived subjectively, when the organism’s existential locus, imposed by humans, is a condemnation to be slaughtered for meat.

Great masses of humans, then, devour tons of meat in their barbecues, in their day-to-day lifes they erect myriads of fast-food joints, staining the landscape with McDonald’s-like signs and ads, without caring about the lives of creatures they deem as unimportant matter. They don’t give a damn about what sort of existence the animals that ended up on their plate, or inside the Big Mac, have lived through from birth to bacon.

“This brings us to the edge of a topic that requires much more discussion than I can give it here: namely, the relation between facts on the one hand and conceptual schemes or systems of representation on the other. (…) Reflection on what it is like to be a bat seems to lead us, therefore, to the conclusion that there are facts that do not consist in the truth of propositions expressible in human language. (…) The more different from oneself the other experiencer is, the less success one can expect with this enterprise. (…) A Martian scientist with no understanding of visual perception could understand the rainbow, or lightning, or clouds as physical phenomena, though he would never be able to understand the human concepts of rainbow, lightning, or cloud, or the place these things occupy in our phenomenal world. (…) Although the concepts themselves are connected with a particular point of view and a particular visual phenomenology, the things apprehended from that point of view are not: they are observable from the point of view but external to it; hence they can be comprehended from other points of view also, either by the same organisms or by others. Lightning has an objective character that is not exhausted by its visual appearance, and this can be investigated by a Martian without vision. And, in understanding a phenomenon like lightning, it is legitimate to go as far away as one can from a strictly human viewpoint.” (NAGEL, Mortal Questions, p. 173)

* * * * *

TO BE CONTINUED…

Buy Mortal Questions by Thomas Nagel

at Amazon.

![Metamorphosis,ThePbk_978-0-393-34709-8[1]](https://awestruckwanderer.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/metamorphosisthepbk_978-0-393-34709-81-e1395800470211.jpg?w=474)